Copyright

From Transformers Wiki

A copyright is the (usually exclusive) right to copy, perform and distribute a work that is an original expression of an idea for a limited period of time. The owner of a copyright can be an individual, a group of people or a corporation. The default owner of the copyright is the creator of the work; however, under United States law, copyright can be transferred or, if the creator was creating his work within the boundaries of a work-for-hire contract, belongs to his employer depending on the exact conditions of the contract. Under US law, a copyright is indicated by a © symbol.

In the context of the Transformers brand, Hasbro and TakaraTomy are the main copyright holders for their respective markets, and they often even act as representatives of the other one in their markets. For example, an American who violates the copyright of something that technically belongs to TakaraTomy will have to deal with Hasbro, who will act on TakaraTomy's behalf. Since most official Transformers-related works are specifically created under work-for-hire contracts, there are very few relevant things Hasbro and/or Takara don't hold the copyrights to, and they will try to amend that as well.

A copyright is not the same thing as a trademark. Since copyrights affect original expression of ideas, it is generally impossible to "copyright" a name, term or slogan, otherwise the simple act of "copying" (i.e. writing it down in a public venue, such as an internet message board) or "performing" it (i.e. saying it aloud in public) would amount to copyright infringement. Names, terms, and slogans are protected as trademarks, which are only relevant in commercial contexts. Graphics and logos can be protected as both trademarks and copyrights (depending on whether they are "original" enough to qualify for copyright protection). Unlike trademark infringement, copyright infringement can be committed by anyone, not just competitors; however, unlike trademark infringement, where the owner has to act as he might otherwise lose his trademark, it is up the owner of a copyright to decide whether he wants to pursue a particular instance of infringement or not. Compared to other companies, Hasbro and TakaraTomy have traditionally shown to be very lenient in this regard when it comes to taking legal actions against their own fans.

Contents |

Copyright history

The concept of intellectual property rights is a relatively new one. During the Middle Ages, nobody would have thought of owning the sole rights to their intellectual works. Stealing a book was considered a crime (which it still is today), but copying a book and leaving the original with its rightful owner was not. Likewise, any sort of music was considered free, and the composers were usually unknown. It wasn't until industrial mass production of creative works came about that a "reproduction monopoly" was established. By the 19th century, many developed countries had their own copyright laws (or comparable concepts) in effect, but those differed widely between the individual countries. In many instances, the creator of a work specifically had to register his work to apply for copyright protection. It wasn't until 1886 that the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (commonly referred to simply as the "Berne Convention"), held in Berne, Switzerland, established an internationally agreed upon, more or less uniform copyright regulation. Any country that had signed the Berne Convention agreed to respect the copyrights of works created in other countries that had also signed it. In addition, copyright protection became an automated process that did not require explicit registration. One of the countries that did not sign the Berne Convention until 1988 (!) was the United States, which is why works still had to be registered to be protected by copyright there until Congress passed a law in 1976 that made registration unnecessary (though registration still comes with additional benefits to this very day). The United States also originally required copyright for a work to be renewed after the original protection term (28 years) had expired, otherwise the work would fall into the public domain; this became automated in 1992.

The purpose of copyright is to entice people to create works and share them with the world. In return, the creators are granted exclusive rights to decide on any uses and reproductions of their work. Essentially, it is a trade-off: Share your work with the world (instead of keeping it to yourself), and you get to decide when and how it is used, published or performed for a public audience (including the right to decide on monetary compensation). Also part of this trade-off is the idea that copyright protection expires after a certain period of time, after which the work irrevocably falls into the public domain and can therefore be copied, performed and published by anyone without requiring permission or payment.

The length of the copyright protection term in the USA has been extended several times. One of the commonly accused culprits is Disney, who repeatedly lobbied Congress to pass a bill that extends the copyright protection term whenever Steamboat Willie is in danger of falling into the public domain. Sonny Bono, a singer-turned-congressman, also pushed hard for one of these extensions in 1998, which is therefore also known as the "Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act". As far as Bono was concerned, copyright protection should ideally last forever (his widow, Mary Bono, who took over his seat in Congress after her husband's death, also quoted then MPAA president Jack Valenti who wanted it to last "forever less one day"), which is in stark contrast to the original purpose of copyright, which did intend for the creator of a work and maybe his heirs to benefit from the revenues generated by the work in question, but certainly not multiple generations of descendants. Imagine the works of Shakespeare, Beethoven, and Leonardo da Vinci were still protected by copyright today. Sure, their heirs would probably love the money, but...

Currently, US copyright protection for works created in or after 1978 lasts for 70 years after the death of the author; work-for-hire creations (see below for more) are protected for 120 years after creation or 95 years after publication, whichever is shorter. The protection for works published or registered in the US before 1978 currently lasts for 95 years starting with the date of publication, as long as the copyright was renewed during the 28th year following the work's publication. That means Steamboat Willie is currently protected by copyright until January 1st, 2024 [1] (unless the law is changed again), although some people claim that it has already fallen into the public domain. Good luck trying to take Disney to court over this, folks. Other countries have their own copyright protection terms, but in most the copyright duration has been extended over the years to either 50 or 70 years after the death of the author. The concept of work-for-hire does not exist in many jurisdictions.

Just to further illustrate how long copyright protection lasts these days: The song "Happy Birthday to You" was composed in 1893 (originally named "Good Morning To All"), with the lyrics written in or prior to 1912 and registered for copyright in 1935. Currently, the Warner Music Group claims ownership of the song, which (with its full lyrics) won't fall into the public domain until 2030 in the USA (2016/17 in the European Union), and Warner still continues to make millions in annual revenue from its use in works such as movies or TV shows. In September 2015, however, a U.S. federal judge ruled that Warner/Chappell Music—the subdivision of WMG involved in the copyright issue—actually did NOT own the copyright to the song, only to a specific piano arrangement of it. This effectively places "Happy Birthday to You" into the public domain, so sing away, everyone.

Modern copyright basics

Any time an original work is created that is an expression of one or more ideas, it is automatically protected by copyright. Ideas themselves cannot be copyrighted; for example, the basic concept "a robot that transforms converts into something else" cannot be copyrighted by itself, neither in terms of toys (anyone can create and release their own transforming toy robots without necessarily committing copyright infringement) nor fiction (anyone can write and publish a story that includes transforming robots without necessarily committing copyright infringement). It is the specific expression of this idea that will be covered by copyright. The limitation for whether something is specific enough to count as on original work covered by copyright or not is known as the threshold of originality. For example, Generation 1 Optimus Prime's toy is protected by copyright, and the same applies to the backstory of the Transformers lore as originally developed by Marvel (alien robots from the planet Cybertron) and the specific stories told in comics, cartoons, video games, and movies. What matters are not specific details by themselves taken out of context, but the work as a whole with all its details in place. The more similar someone else's work is to these specific works, the more likely that person or party will be found guilty of copyright infringement. The more vague the similarities are, or the more general the idea supposedly copied, the less likely the person or party will be convicted. (It's not really possible to quantify similarities in percents, though. Copyright disputes are decided on a case-by-case basis.)

The default owner of a copyright is the creator of the work. If a work is created as a group effort by several people, they share the copyright to the work, or hold the copyright to certain parts of it. For example, if Jim composes a song and Bill writes lyrics to go along with the tune, Jim owns the copyright to the melody (which includes the right to reproduce written notes!), whereas Bill owns the copyright to the lyrics (which also includes written reproductions). That means Jim is free to release the song as long as he doesn't use Bill's lyrics, and Bill can use the lyrics as long as he doesn't use them with Jim's music. If they shared the workload for one or more steps, they share the copyright and need to reach an agreement when it comes to releasing or licensing their shared work.

It is also possible to create a work under a work-for-hire contract for a company, which is the default in the American entertainment industry (creator-owned works are the exception rather than the rule). Anything created under the conditions of such a contract is usually copyrighted to the company. When Hasbro assigned Marvel to develop a backstory for the then upcoming new Transformers series, Marvel was working under a work-for-hire contract for Hasbro, and Marvel's employees were working under a work-for-hire contract for Marvel. That means any stories, characters and concepts they created within the boundaries of their contracts were automatically copyrighted to Hasbro, not to Marvel or the individual creators. Marvel tried to circumvent that eventuality for a few characters due to a loophole in the contract, however (see below for more details). It is also possible to transfer copyright ownership to a new owner by means of a contract. For example, when Hasbro acquired the license to sell Takara's Diaclone and Micro Change toys on the United States market under the name The Transformers, they became the de facto copyright holder to the toys for the US market.[2] All modern, jointly-created Transformers toys are shared properties of Hasbro and TakaraTomy according to the copyright markings found on the individual toys.

Infringement and defending copyrights

Any unauthorized use of a work that is protected by copyright constitutes copyright infringement, and can result in legal prosecution. A common misconception is that "anything that can be found on the internet is free". Any images found on the internet are by default protected by copyright, and therefore cannot legally be copied and republished without permission. Exceptions are works that are in the public domain, either because the copyright term has expired, the work has been created by an employee of the United States government and military within the boundaries of their employment (those are in the public domain by default), or because the creator has deliberately released his work into the public domain (which is irrevocable). There are also specific licenses (Creative Commons, Copyleft, GNU General Public License etc.) which allow individuals to use someone else's work without specific permission as long as the conditions of the license are respected (e.g. identifying the creator by name, non-commercial use only, etc.). However, even though any unauthorized republication of a promotional image depicting Optimus Prime constitutes a copyright violation (which means pretty much any internet fan site is full of copyright violations), it is ultimately up to the copyright holder to decide whether he wants to legally pursue a specific instance of copyright violation or not. Unlike trademarks, looking the other way and pretending not to notice a copyright violation does not put the owner in danger of losing his intellectual property.

An exemption is a concept known as "fair use" that exists in United States copyright law, but is legally unknown in many other countries. "Fair use" basically constitutes that using a reasonable excerpt of someone else's work (a small-scale version of an image, an excerpt from a text etc.) within the context of a new, original work does not constitute a copyright violation depending on the context of intended use. Non-profit informational purposes are a popular reason to invoke fair use. Criticism and parodies of the work itself are also generally covered by fair use; however, the new work in whose context the copyrighted work is used must contain a certain amount of originality. Simply showing a scene from a movie does not constitute fair use; showing a scene from a movie and pointing out the filmmaking techniques used in the creation of the scene, commenting on the effect the scene has on its target audience or making fun of flaws in the scripting, set decoration, performance and direction of the scene would be more likely to fall under the fair use exemption. Note that "fair use" is often invoked by internet fan sites to excuse massive amounts of copyright violations—the conditions for when "fair use" applies are actually a lot stricter than is commonly assumed.

Hasbro and TakaraTomy have a long history of being very lenient when it comes to the fans of their brand. The owners of Asterix are known to be particularly rigid when it comes to defending their intellectual property (especially in Europe, where copyright law is even more rigid than in the US in many regards, and the concept of "fair use" is unknown). Compared to that, Hasbro and TakaraTomy's approach appears to be based on several questions: Is the copyright violator acting in bad faith? Does the copyright violator make a profit? Does the copyright violation reasonably cause actual (instead of just purely hypothetical) damage? Does the damage averted by legal measures outweigh the efforts and expenses for those legal measures? Do legal measures hurt the public image by appearing as an evil corporation that takes its own customers to court? Note that there is a large leeway for copyright holders to operate in. The record and movie industry often prefer to hold their target audience on a short leash, whereas and Hasbro and TakaraTomy have opted for the fan-friendly end of the spectrum. Fans occasionally excuse the content of fan sites by arguing that they are effectively "free advertising" for theTransformers brand—however, while this mindset certainly influences Hasbro and TakaraTomy's actions in this regard, "free advertising" is by no means a valid legal defense.

Hasbro and TakaraTomy are doing so by their own choice and are free to change their approach whenever they want. For example, in the early 2000s, several fan sites were hosting scans of the Generation 1 Marvel comics and encodes of the Sunbow cartoon. Neither were officially being distributed back then, and for whatever reason, Hasbro did not take legal action against those materials being openly offered on the internet for several years. However, with the onset of a general 1980s nostalgia wave and an increasing interest in Transformers in general, Titan started releasing collected editions of the Marvel comics, and Kid Rhino released the cartoon on DVD. Around the same time, the owners of these websites had started to ask for donations to cover their bandwidth fees. Whatever the specific reason, Hasbro eventually sent out cease and desist orders, a comparably harmless legal measure. The sites in question complied and removed the content in question, prompting Hasbro to continue tolerating their existence and other, comparably minor copyright violations.

Knockoffs of Hasbro's toys also constitute copyright violations. This was confirmed in two court cases from 1985, namely Hasbro Bradley, Inc. v. Sparkle Toys, Inc.[3] and Wales Indus. Inc. v. Hasbro Bradley, Inc.[2] There are no records of Hasbro shutting down knockoff operations from 1990 onwards, as the problem is that the manufacturers of knockoffs are usually located in countries like China, and taking legal action against copyright violation in other countries tends to be a lot more expensive than against domestic operations. In addition, despite having finally signed the Berne Convention in 1992, there are still many instances of Chinese authorities not enforcing international copyrights as thoroughly as foreign copyright holders would like them to. Thus, it's easier for Hasbro to go after domestic distributors or simply urge retailers to stop selling knockoffs. They don't even need to threaten legal action—threatening to stop supplying the store in question with official Hasbro product can be more than sufficient. Despite this, knockoffs still continue to find their way into American stores.

Derivative works

A more complicated concept are "derivative works". Those are new works which are based in part on other works, to which the creator of those new works does not hold the copyright. A derivative work is not an outright copyright infringement, since it constitutes a new work that contains original expressions of ideas. However, it is not an entirely independent work either, since it contains elements of other works. If those other works are in the public domain, the creator of the new work does not have to fear litigation, and his new work is protected by copyright. Simply put, Marcel Duchamp's painting L.H.O.O.Q. is based on the Mona Lisa, but since the Mona Lisa is already in the public domain, Duchamp did not encounter any legal problems. Another painting also based on the Mona Lisa could easily coexist with L.H.O.O.Q.; but another painting that is a direct copy of L.H.O.O.Q. would constitute a copyright infringement under French law (but not under US law, since Duchamp's painting has fallen into the public domain there as well).

If the earlier work is still protected by copyright, it's possible for the copyright holder(s) to take legal action against the creator of the derivative work. Aside from the possibility of financial compensation, they may also prohibit any further distribution of the derivative work. The copyright holder of the earlier work does not, however, gain the sole copyright to the derivative work. Simply put, the creator of the derivative work cannot distribute his work without permission from the copyright holder of the earlier work; but the copyright holder of the earlier work cannot distribute the derivative work without permission from its creator either.

There are no cut-and-dry rules for what exactly constitutes a derivative work. Generally, any fanfic based in the Transformers universe that uses existing characters, settings and plot elements is a derivative work. A fanfic about shape-shifting alien robots that does not use any established names and contains only vague references to established Transformers lore would be much harder to judge. The same accounts for fanart: A drawing that depicts Optimus Prime based on his animation model constitutes a derivative work, but a drawing that depicts a red and blue robot with truck kibble and a head reminiscent of Optimus Prime, but is not based on a preexisting design, is less certain. However, selling fanart for a profit can also result in additional problems if the artwork in question contains any names or logos that are trademarked by Hasbro. Likewise, toy robots that are based on existing Transformers toys and only change some details such as adding a new head, altering some parts etc. would constitute derivative works, or even plain out copyright infringement depending on how minor the alterations are. Scratch-built toys based on existing characters, but not based on existing toys and either based on designs from comics or cartoons with no toy counterpart, or even entirely made up, would qualify as derivative works, because adapting a 2D design into a functional 3D toy constitutes a creative process that qualifies as an original expression of ideas. In Transformers-related terms, that means most, if not all "third party third party toys" are either derivative works or flat out copyright violations depending on their similarities to existing toys (excluding Japanese garage kit toys whose creators acquired a one-day license from TakaraTomy for selling their products at a convention). Likewise, knockoffs are usually copyright violations (as mentioned above), while some of the more "creative" ones might qualify as derivative works.

Even customized toys that are sold for a profit can be considered derivative works. In 2011, two Japanese hobbyists were arrested for auctioning a customized Kamen Rider figure, which Bandai holds the copyright to.[4] However, Hasbro and TakaraTomy are more lenient in this regard. Even though there are rumors that Hasbro will start to go after unlicensed third-party products every few months, nothing ever comes out of it. Third-party products are openly displayed by various sellers at BotCon in plain sight of Hasbro, and even though some fans insist on asking Hasbro about third-party products at every BotCon panel, Hasbro have tried to dodge the issue, referring to their copyrights and generally just trying to ignore those third-party products' existence. However, during the preparations for BotCon 2015, organizer Fun Publications have informed dealers about a general ban on those unlicensed derivative figures, while explicitly insisting fans not to refer to them as "third party products". Likewise, Hasbro and Takara normally do not take legal action against fan fiction and fanart.

Copyright conflicts in the Transformers brand

Even though most creative works in relation to the Transformers brand are created under a work-for-hire contract (or an equivalent arrangement in countries where the concept of "work-for-hire" does not exist) for either Hasbro or Takara/TakaraTomy, there are a few instances where the copyright to a work, or at least parts of it, is not the sole property of either company.

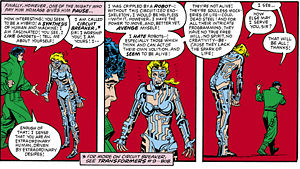

- The original work-for-hire contract between Hasbro and Marvel apparently stated that any character whose first appearance was in a Transformers-branded comic automatically became the property of Hasbro, regardless of whether the character was based on an existing toy or not. For that reason, Bob Budiansky had Circuit Breaker appear in Marvel's non-Transformers comic Secret Wars II #3 (cover date September 1985) before her "real" debut in The Transformers issue 9 (cover date October 1985) so Marvel could keep ownership of the character.[5] Curiously enough, Circuit Breaker's human identity, Josie Beller, already debuted in The Transformers issue 5 (cover date June 1985), but this probably makes more sense to lawyers.

- Likewise, the story goes that Death's Head first appeared in a single-page strip named "High Noon Tex" (written "on a napkin"[6] by Simon Furman, with artwork by Bryan Hitch) that was published in various Marvel UK titles before the character appeared in issue 113 of the Marvel UK Transformers comic—thus granting Marvel ownership of the character and allowing them to give him his own comic entirely independent from the Transformers. However, Hitch's signature is dated to 1988, apparently after his earliest work on Transformers[7] and certainly after Death's Head's debut, and no evidence of a Marvel publication containing the strip prior to 1988 has ever surfaced—meaning that more likely, someone told a little fib to keep the character under contract. Can hardly blame them, yes?

- More problematic are G.B. Blackrock and the Neo-Knights: From issue 74 through 80 of the Marvel US Transformers comic, Marvel claimed the names "Circuit Breaker", "G.B. Blackrock", "Thunderpunch", "Rapture", "Dynamo" and "the Neo-Knights" as trademarks. One of the problems here is that they never used most of these names in commerce (in advertising, on covers etc.), so they didn't really have a trademark claim on them. Marvel did, however, believe that they owned the copyright to those characters, as Simon Furman intended to rework the Neo-Knights and give them their own title, "Techno-X", after the Transformers comic had been cancelled. The project never actually came to pass, however.[8] G.B. Blackrock is particularly questionable, as he had first appeared in issue 5 of the Marvel Transformers comic, and had not been given the "appearing in a different Marvel title first" treatment, thus making Marvel's claim to the character highly questionable. Despite this, these characters which Marvel claimed ownership of made reprints of any comics they appeared in problematic. Titan's paperback collections were apparently not affected, either due to different copyright laws in the United Kingdom or because they had reached an agreement with Marvel; however, United States-based publisher IDW's reprints in titles such as Generations, Best of UK and Classic Transformers had to skip any issues that featured the "Marvel" characters, until Hasbro and/or IDW reached an agreement with Marvel (possibly in the wake of Hasbro acquiring the license for Marvel toys in 2006) which allowed them to reprint those issues as well starting with Classic Transformers Volume 5.

- Raksha, the creator of the BotCon 1995 exclusive Nightracer toy's character, maintains that since the character's name, personality, and bio never went through the official Hasbro approval process, Hasbro has no legal claim on the character. The claim is shaky at best, due to the nature of derivative works, but Hasbro has yet to pursue the issue, and is unlikely to do so in the future. As such, Nightracer holds a rather unique position; the toy is official, but the character is not. Kinda. (Raksha, the creator of the character, subsequently wrote the bio for another Nightracer toy that was released as part of Fun Publications' Transformers Figure Subscription Service, presumably this time with Hasbro's approval.)

- When Hasbro took over Tonka in 1991, they acquired the trademarks to the name "GoBots" and related characters, but not the copyrights, which eventually fell back to Japanese licensor Bandai. The situation became even more complicated in Japan, where Takara intended to release redecos of the Transformers Collection Minibot Team reissues through e-HOBBY in 2004 intended as Tonka GoBot homages. Even though the individual toys were identified by name in early promotional material, the released set was officially called "Dimension Exploration Researchers" (with the bio card calling them "G1 GoBots"), but the individual toys were not referred to by name in the included paperwork to avoid conflict with Bandai. This was more of an extreme precaution on Takara's behalf rather than in response to actual threat of legal action on Bandai's behalf, however.[9]

- For unknown reasons, the Sunbow cartoons based on Hasbro properties, such as The Transformers, G.I. Joe, and others, did not originally become Hasbro's sole property. Instead, Sunbow's assets were bought out by Sony Wonder in 1998 and subsequently sold to German-based TV-Loonland in 2000. As a consequence, Loonland held the worldwide distribution rights to the Transformers cartoon for several years until the company encountered financial problems and subsequently sold the entire Hasbro-related Sunbow back catalog to Hasbro for a mere US$7 million total, thus finally giving Hasbro the sole worldwide distribution rights to those shows.[10]

- Saban was responsible for the English Robots in Disguise dub of the Japanese Car Robots cartoon. Subsequently, Saban was purchased by Disney. Due to their ownership claim of the English dub, Robots in Disguise has still not been released on DVD in the United States. (It has, however, been released in the United Kingdom several times by this point.)

- The unfinished Dreamwave plotlines are currently still unlikely to ever be resolved by another publisher (such as IDW). Even though writers Adam Patyk and James McDonough worked under a work-for-hire contract, they maintain that they are still owed payment for their work and thus Dreamwave has failed to fulfill its side of the contract, and therefore they currently still claim ownership of those stories until they receive compensation.[11]

- The live-action film series is not Hasbro's sole property. The licensing agreement with DreamWorks and Paramount makes anything related to the movie-verse (including any toys based on characters that appear on-screen) at least partially their property as well.

Copyright markings

All official Transformers toys feature engraved copyright markings, also known as copystamps, somewhere on the toy. Aside from legal protection against knockoffs, this also complies with legal requirements for identifying the manufacturer of a toy for the sake of potential litigation in case someone might get injured while playing with a toy.

For toys that consist of multiple components, the copyright markings are typically located on the largest component. This makes sense for toys with smaller accessories such as weapons, missiles or combiner kibble (in the original meaning of the term), as it would seem a little excessive to have copystamps on every single piece of accessory. However, in some cases this gets a little more problematic: For example, Generation 1 Optimus Prime's copyright markings are located on the underside of the trailer. If one were to check the cab/main robot for its copyright markings, this would pose a problem. In some instances, the copystamps are also located in considerably well-hidden spots: Revenge of the Fallen Legends Class Bumblebee has his on the underside of his roof, almost impossible to see from most angles.

Copyright markings have changed a lot over the years. 1984 Generation 1 toys that originated from the Micro Change and Diaclone lines initially only had Takara copyright markings. Additional Hasbro copyrights were added for 1985 releases (including toys already released the previous year which were still shipping). Due to different rules for Japanese copyright law back in the day, the Micro Change-derived toys tended to have two years listed, the first of them (1974 for Micro Change, 1980 for Diaclone) referring to the year the toy line/franchise was originally launched, the other one referring to the year the toy in question was actually designed. Therefore, a Generation 1 Megatron toy with a "1974, 1983" copyright does not mean that the Megatron design dates back to 1974; rather, it means that the toy was first released in Japan in 1983, as part of a toy line that was originally launched in 1974. Also starting in 1985, all toys that had never been officially released in Japan before being released by Hasbro under the Transformers brand only featured the year of the toy's release in their copystamp, presumably because Transformers was originally an American brand and thus not bound by Japanese copyright law.

The markings were further changed in 1985, now identifying Takara as "Takara Co. Ltd" instead of simply "Takara". By 1987, "Hasbro" was changed to "Hasbro, Inc.". Some Generation 2 re-releases of Generation 1 toys had their copystamps further modified and no longer mentioned Takara at all. None of the toys in question were available in Japan, although toys only released by Hasbro usually still sport dual company copystamps. For the 2000-onwards reissues, Takara used whatever molds were available, which means that some toys last released under Generation 2 still sported Hasbro-only copyright markings for their Japanese market reissues. Meanwhile, toys designed by Takara and initially only released in Japan such as Deathsaurus or the Micromaster Sixteams only sport Takara markings, although for their much later Hasbro release under the Universe banner, the latter were given additional tampographed Hasbro copyright markings. By the time of Beast Wars, the copystamps once again only identified the Japanese company as "Takara".[12]

Licensed vehicle alternate modes sport additional markings that identify them as such. Those can vary in length: For example, Alternators Autobot Hound is marked "Jeep® Wrangler® DCC 2003", his retool Swindle sports an even longer "Jeep® Wrangler® ©DaimlerChrysler 2004"; conversely, toys from the live-action film series with alternate modes licensed by General Motors simply sport "TMGM" markings.

Occasionally, Hasbro and Takara would cast new toolings based on the same sculpt to fight the effects of mold degradation. A prime example is the Classics Deluxe Starscream sculpt, of which at least three known versions exist (not even counting new parts such as for the Ramjet "retool"), which can be told apart by very minor differences in the sculpted details. Usually, the new tooling would get a new year for the Hasbro copyright, while the Takara copyright year remains the same. Thus, Classics Starscream has "© 2006 Hasbro, Inc. © Takara 2006" copystamps, whereas his Universe redeco, which uses one of the newer toolings, has "© 2008 Hasbro, Inc. © Takara 2006". However, since Hasbro later used the original tooling again, Generations Dirge sports "© 2006 Hasbro, Inc." markings again.

Following Takara's merger with Tomy into TakaraTomy, the copyright markings stated the company's name simply as "Tomy" starting in 2007. Hasbro's name was changed from "Hasbro, Inc." to "Hasbro SA" (South Asia) in 2011, dropping the year entirely for both companies and the copyright © symbol for Hasbro, which also applies to further uses of existing toolings, which are modified accordingly

Notes

- The correct spelling is copyright, as in "the right to copy", not "copywrite". Likewise, the past tense is "copyrighted", not "copywritten". There is such a thing as a copywriter, but that is not directly related to this article's subject.

- Copyright and trademark are two different things! Seriously! Copyright covers the content of a work, whereas trademark covers the name a work is marketed under, among other things. You cannot "copyright" a name!

- Also different from copyright are design patents. Takara has been patenting Transformers toys ever since the days of Generation 1. Patents still need to be registered in order for them to be granted legal protection. Patents have a maximum protection of 20 years, but they only affect the functionality of a toy, while its look is separately protected by copyright. In other words, you can design your own toy which transforms exactly like Generation 1 Optimus Prime now, but it must not resemble the fictional character Optimus Prime in terms of aesthetics. This is probably why there have been dozens of off-brand toys based around the Jumpstarters' concept over the years without actually resembling Topspin or Twin Twist.

See also

References

- ↑ STEAMBOAT WILLIE GOES PD, THE MOUSE NOT SO MUCH

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 WALES INDUS. INC. v. HASBRO BRADLEY, INC. and supplementary item at Leagle.com.

- ↑ HASBRO BRADLEY, INC. v. SPARKLE TOYS, INC. at the Legal Information Institute

- ↑ "2 Arrested for Selling Modified Kamen Rider Figure"

- ↑ BWTF interview with Bob Budiansky, 2004.

- ↑ "Draw Death's Head Day cometh & he's 35 years young so here's another fabuloso DH fact: High Noon Tex was fast-tracked to make DH a Marvel character, written on a napkin by me and drawn overnight by 16-year old @THEBRYANHITCH at a UKAC*. https://t.co/8QWJKu3rCy *UK Comic Art con https://t.co/QwqytCfnAt"—Simon Furman, Twitter, 2022/03/16

- ↑ "@SimonFurman3 I'm pretty sure I was 17, maybe about to be 18. I was 16 when you and Starkers first gave me the Action Force work and turned 17 whilst doing that first story. So I was 17 when I did the first Transformers work and DH came a little after that. I was much older..."—Bryan Hitch, Twitter, 2022/03/16

- ↑ WILDFUR Update - What Could Have Been... Techno X at TFW2005.

- ↑ Explanation of the individual name removal by Hirofumi Ichikawa

- ↑ TV Shows on DVD article, "Transformers - Hasbro Pays US$7 Million to Reacquire Distro Rights to Transformers, G.I. Joe & Others!"

- ↑ McDonough and Patyk commenting on the lack of closure to their Dreamwave plotlines at TFW2005

- ↑ "Mark of the TAKARA", crazysteve's Transformer Stampings page