Abstract

Background

Scrub typhus, an acute febrile disease with mild to severe, life-threatening manifestations, potentially presents with a variety of complications, including pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiac arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation), myocarditis, shock, peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, meningitis, encephalitis, and renal failure. Of the various complications associated with scrub typhus, splenic rupture has rarely been reported, and its mechanisms are unknown. This study reports a case of scrub typhus-related spontaneous splenic rupture and identifies possible mechanisms through the gross and histopathologic findings.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old man presented to our emergency room with a 5-day history of fever and skin rash. On physical examination, eschar was observed on the left upper abdominal quadrant. The abdomen was not tender, and there was no history of trauma. The Orientia tsutsugamushi antibody titer using the indirect immunofluorescent antibody test was 1:640. On Day 6 of hospitalization, he complained of sudden-onset left upper abdominal quadrant pain and showed mental changes. His vital signs were a blood pressure of 70/40 mmHg, a heart rate pf 140 beats per min, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per min, with a temperature of 36.8 °C. There were no signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. Grey Turner's sign was suspected during an abdominal examination. Portable ultrasonography showed retroperitoneal bleeding, so an emergency exploratory laparotomy was performed, leading to a diagnosis of hemoperitoneum due to splenic rupture and a splenectomy. The patient had been taking oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) for 6 days; after surgery, this was discontinued, and intravenous azithromycin (500 mg daily) was administered. No arrhythmia associated with azithromycin was observed. However, renal failure with hemodialysis, persistent hyperbilirubinemia, and multiorgan failure occurred. The patient did not recover and died on the fifty-sixth day of hospitalization.

Conclusions

Clinicians should consider the possibility of splenic rupture in patients with scrub typhus who display sudden-onset abdominal pain and unstable vital signs. In addition, splenic capsular rupture and extra-capsular hemorrhage are thought to be caused by splenomegaly and capsular distention resulting from red blood cell congestion in the red pulp destroying the splenic sinus.

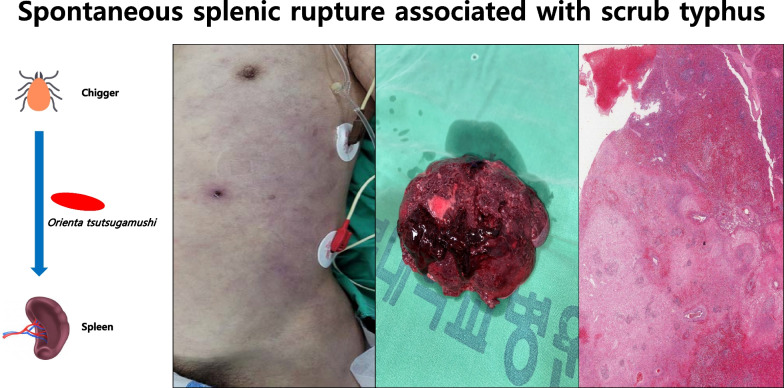

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Scrub typhus, Complication, Splenic rupture

Background

Scrub typhus is an acute, febrile, infectious disease caused by the obligate intracellular bacillus Orientia tsutsugamushi [1]. It is transmitted via the bites of chigger mites and leads to generalized or localized vasculitis that can involve any organ(s) [2]. Scrub typhus is a serious public health problem in the Asia–Pacific region, threatening a billion people globally, and there are a million cases each year [3]. Its manifestations range from mild to severe and life-threatening, and can be accompanied by various complications, such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiac arrhythmias (such as atrial fibrillation), myocarditis, shock, peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal bleeding, meningitis, encephalitis, and renal failure [2]. The lungs are one of the main target organs for O. tsutsugamushi, leading to pulmonary complications of variable severity, and interstitial pneumonia may occur [1, 4]. Meningoencephalitis or encephalopathy can develop, resulting in agitation, delirium, or even have seizures [5]. Myocarditis can lead to cardiogenic shock, and while cardiac arrest has rarely been reported, recently the incidence seems to be increasing [6].

Among the various scrub typhus-related complications, splenic involvement, such as splenic rupture or splenic infarction, has been reported as rare [7]. Two cases of splenic rupture associated with scrub typhus have been reported in MEDLINE, 1 in PubMed and 1 in KoreaMed [8, 9]. The mechanism of scrub typhus-related splenic rupture is unknown. This study reports a case of spontaneous splenic rupture associated with scrub typhus in the Republic of Korea and identifies the possible mechanisms through the gross and histopathologic findings.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old man presented to our emergency room with a 5-day history of fever and skin rash. His occupation was farming, and he predominantly grew peppers. On admission, his initial vital signs were a blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, a heart rate of 88 beats per min, a respiratory rate of 16 breaths per min, and a temperature of 38.3 ℃. Physical examination by the emergency medical personnel revealed eschar on the left upper abdominal quadrant (Fig. 1). The patient was alert, and the neurological examination did not reveal any deficits. There was no cardiac murmur upon auscultation, and breath sounds were heard equally on both sides. His abdomen as a whole was not tender, and there was no history of trauma. His laboratory results were as follows: white blood cell count, 7.62 × 103/μl (69.9% neutrophils); hemoglobin, 10.5 g/dL; platelet count, 74 × 103/μl; alkaline phosphatase, 319 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, 115 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.74 mg/dL; aspartate transaminase (AST), 190 IU/L; alanine transferase (ALT), 113 IU/L; total protein, 5.1 g/dL; albumin, 3.2 g/dL; blood urea nitrogen (BUN), 43 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.76 mg/dL; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), 824 IU/L; C-reactive protein, 189 mg/L; and procalcitonin, 1.03 ng/ml. The patient had not traveled abroad in the past year. Serology for the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) indicated a previous EBV infection (negative VCA IgM, positive VCA IgG, negative early antigen antibody, and positive EBV nuclear antigen antibody). There was no evidence of malaria in the peripheral blood smear. The O. tsutsugamushi antibody titer using the indirect immunofluorescent antibody test was 1:160, and this increased to 1:640 in the follow-up test after 2 weeks. The patient was clinically diagnosed with scrub typhus and started taking oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily) from the first day of admission.

Fig. 1.

Eschar on the left upper abdomen quadrant (arrow)

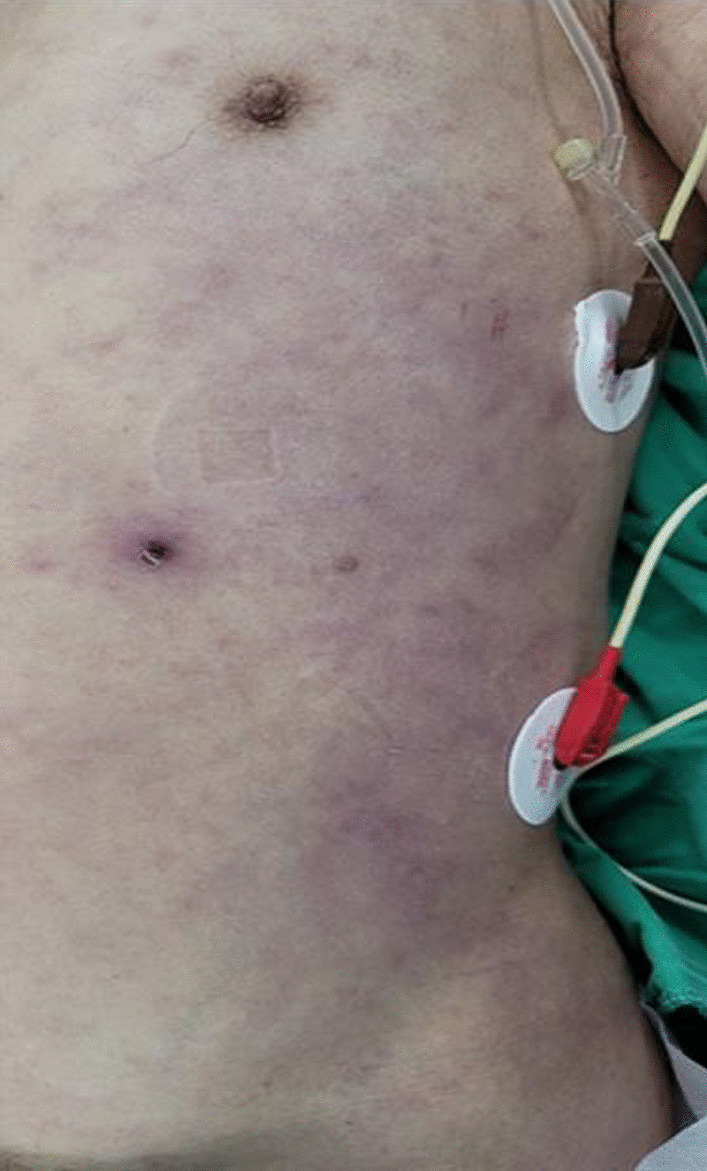

On Day 6 of hospitalization, the patient complained of sudden-onset left upper abdominal quadrant pain and showed mental changes. Patient was drowsy. He was not oriented, but was following commands. There was no cardiac murmur upon auscultation, and breath sounds were heard equally on both sides. During abdominal examination, direct tenderness was observed throughout the entire abdominal area. His blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg, heart rate 140 beats per min, respiratory rate 20 breaths per min, and temperature 36.8 ℃. He was transferred to the intensive care unit. The laboratory analysis performed immediately in the intensive care unit showed white blood cell count, 17.82 × 103/μl (54.8% neutrophils); hemoglobin, 4.9 g/dL; and platelet count, 76 × 103/μl. No signs associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia, were observed. While preparing for an abdominal computed tomography (CT) to evaluate the patient’s pain, the patient went into ventricular tachycardia. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was done for 10 min and return of spontaneous circulation was achieved. Echocardiography performed after CPR showed near-normal left ventricular systolic function (ejection fraction 53%), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (E/E’ ratio 13), mild resting pulmonary hypertension, and a small amount of pericardial effusion without hemodynamic significance. Abdominal CT was not done. Grey Turner's sign was suspected due to discoloration of the left flank on abdominal examination (Fig. 2), and portable ultrasonography revealed retroperitoneal bleeding, so an emergency exploratory laparotomy was undertaken. Based on the operative findings, hemoperitoneum due to splenic rupture was diagnosed and a splenectomy was performed.

Fig. 2.

Grey Turner’s sign indicating bruising of the left flank

Figure 3 shows the macroscopic findings from the patient’s ruptured spleen. The capsule of the dorsal surface of the spleen was torn, the spleen parenchyma was exposed, and coagulated blood clots were present along with bleeding in the ruptured area (Fig. 3A). The hilum capsule of the spleen showed no abnormalities (Fig. 3B). Histopathology of the ruptured spleen revealed various types of injuries (Fig. 4A): infarction of the splenic tissue (Fig. 4B), red pulp of the spleen showing destruction of the splenic sinus with red blood cell congestion (Fig. 4C), and subcapsular hemorrhage (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic findings of a ruptured spleen. A The capsule of the dorsal surface of the spleen was torn, the spleen parenchyma was exposed, and coagulated blood clots were present along with bleeding in the ruptured area. B The hilum capsule of the spleen; no abnormalities were detected

Fig. 4.

Histologic features of spleen. A Lower-power field of the spleen showing various types of injuries (H&E stain, original magnification: × 20). B High-power view of the faintly eosinophilic area in Figure A reveals infarction-type necrosis in the splenic tissue (H&E stain, arrow, original magnification: × 200). C Higher magnification on the hemorrhagic area of Figure A reveals the destruction of red pulp and congestion of red blood cells (H&E stain, arrow, original magnification: × 200). D High-power view of the splenic capsular region showing subcapsular hemorrhage (H&E stain, arrow, original magnification: × 200)

After emergency surgery, oral doxycycline was terminated, and intravenous azithromycin (500 mg daily for 6 days) was administered along with intravenous vancomycin (750 mg q 72 h) and meropenem (500 mg q 24 h). Intravenous vancomycin and meropenem were administered for 14 days. During hospitalization, no bacteria were identified in the patient’s blood culture. There was no recurrence of ventricular tachycardia, and no arrhythmia associated with azithromycin was observed. However, renal failure with hemodialysis, persistent hyperbilirubinemia, and multiorgan failure occurred from the next day after surgery and persisted during hospitalization. He did not recover from these conditions and died on the fifty-sixth day of hospitalization.

Discussion and conclusions

This study reports a patient with spontaneous splenic rupture associated with scrub typhus and, for the first time, presents the corresponding gross and histopathologic findings. Abdominopelvic involvement is not uncommon in patients with scrub typhus [7]. However, splenic rupture and splenic infarction as splenic complications associated with scrub typhus have been reported as rare [1, 7, 10, 11]. According to a systematic review of 845 patients with atraumatic splenic rupture, of the infectious disorders associated with splenic rupture, infectious mononucleosis is the most common, followed by malaria [12]. Another study reported the incidence of splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis as 0.1% [13]. However, the estimated incidence of malaria-induced spleen rupture is 0.12%, and malaria is considered the most frequent cause of pathological splenic rupture worldwide, although the true incidence of pathological splenic rupture in natural vector-transmitted malaria is unknown [14, 15]. To date, the incidence of scrub typhus-related splenic rupture is also unknown. In three radiologic studies on scrub typhus, the frequency of splenic infarction was presented as 3.8% [7], 6.4% [11], and 16% [1]. Therefore, although there are limitations in assessing the incidence of scrub typhus-related splenic rupture, it is estimated to be lower than the risk of scrub typhus-related splenic infarction and splenic rupture in either infectious mononucleosis or malaria.

We reviewed the relevant literature discussing splenic rupture associated with scrub typhus by searching for “spleen rupture, scrub typhus” in MEDLINE/PubMed and KoreaMed (https://koreamed.org/). The two reported cases survived, but our patient died despite undergoing a splenectomy. Table 1 presents the clinical characteristics of the three cases. There were nine cases of scrub typhus-related splenic infarction reported in PubMed and KoreaMed [16–22]. Table 2 compares the clinical characteristics of the nine cases of splenic infarction and the three cases of splenic rupture. There were no statistically significant differences in the median time from symptom onset to splenic complications between the two groups (P = 0.402). All the patients with splenic infarction recovered with only medical treatment, but the splenic rupture cases were more likely to need surgical treatment, such as a splenectomy, because splenic rupture can be severe and life-threatening [12].

Table 1.

The clinical feature, treatment, and outcome of patients with scrub typhus-related splenic rupture

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Present case | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 74 years | 75 years | 78 years |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male |

| Abdominal pain | Yes (right side pain) | Yes (LUQ pain) | Yes (LUQ pain) |

| Blood pressure | 109/93 mmHg | 110/70 mmHg | 70/40 mmHg |

| Heart rate | 120 beats/min | 88 beats/min | 140 beats/min |

| Hemodynamic instability | Yes | No | Yes |

| Time from the onset of symptom to diagnosis of splenic rupture | 5 days | 14 days | 11 days |

| Treatment | |||

| Antibiotics, duration (day) | Chlorampenicol (PO, 1 day), doxycycline (PO, 6 days) | NA | Doxycycline (PO, 6 days) Azithromycin (IV, 6 days) |

| Medical treatment | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Splenectomy | Done | Not done | Done |

| Outcome | Alive | Alive | Death |

NA not available, PO per oral, IV intravenous, LUQ left upper quadrant

Table 2.

Comparison of splenic infarction and splenic rupture in scrub typhus

| Splenic rupture (n = 3) | Splenic infarction (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain or diffuse abdominal tenderness | 3/3 | 8/9 |

| Time from symptom onset to splenic complications, days, median (range)a | 11 (5, 14) | 7 (3, 15) |

| Only medical treatment | 1/3 | 9/9 |

| Splenectomy | 2/3 | 0/9 |

| Death | 1/3 | 0/9 |

The figures in each cell refer to the number of subjects occurring among the total number of patients

aMann–Whitney U test was used to assess time from symptom onset to splenic complications between 3 (3/3) patients with splenic rupture and 8 (8/9) patients with splenic infarction (P = 0.402)

To date, the mechanisms of scrub typhus-related splenic rupture have not been reported. Discussions regarding the concrete mechanisms of splenic rupture are limited because there are insufficient data about the underlying disease, as well as laboratory and pathological findings related to splenic rupture caused by scrub typhus. However, Kim et al.’s study suggested that intrasplenic pseudoaneurysm is one of the mechanisms [9]. Based on our study’s pathological findings, we hypothesize a sequence of events that could lead to extra-splenic hemorrhage: massive red blood cell congestion, which distorts and destroys the structure of the splenic sinus, and splenic infarction increase the volume of the red pulp and put pressure on the capsule, leading to capsular distension, rupture, and ultimately extra-splenic hemorrhage. This mechanism is similar to that of malaria-related splenic rupture [14]. Macroscopic investigations of splenomegaly found the capsule on the hilum side to be dilated, the capsule on the other side to bear a degloving injury, and the spleen parenchyma exposed to the abdominal cavity. Ischemic changes and capsular rupture meant the spleen appeared almost purple in color. This suggests that splenomegaly and capsular distention contribute to extra-splenic hemorrhage [14].

In summary, we report a patient with spontaneous scrub typhus-related splenic rupture. Clinicians should consider the possibility of splenic rupture in patients with scrub typhus who present with sudden-onset abdominal pain and unstable vital signs. We hypothesize that capsular rupture and extra-capsular hemorrhage result from splenomegaly and capsular distention, themselves caused by red blood cell congestion in the red pulp distorting and destroying the splenic sinus.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT

Computed tomography

- ROSC

Return of spontaneous circulation

- LV

Left ventricle

- EF

Ejection fraction

- LVEDP

Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure

- EAL

Early antigen

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- EBNA

EBV nuclear antigen

Author contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. JHH and HPH conceptualized the study. JHH and HJH treated the patient. KMK designed and performed the experiments. HPH performed the splenectomy. KMK, HJH, and HPH analyzed the data. JHH, HJH, HPH, and KMK wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript, and read and approved the final version.

Funding

This paper was supported by the Biomedical Research Institute’s fund at Jeonbuk National University Hospital. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting this study’s the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved and performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB No.: CUH 2023-07-021).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors of this study declare no commercial relationships and no competing interest.

Footnotes

Hong Pil Hwang and Kyoung Min Kim contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hyojin Han, Email: [email protected].

Jeong-Hwan Hwang, Email: [email protected].

References

- 1.Jeong YJ, Kim S, Wook YD, Lee JW, Kim KI, Lee SH. Scrub typhus: clinical, pathologic, and imaging findings. Radiographics. 2007;27:161–172. doi: 10.1148/rg.271065074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim MH, Kim SH, Choi JH, Wie SH. Clinical and laboratory predictors associated with complicated scrub typhus. Infect Chemother. 2019;51:161–170. doi: 10.3947/ic.2019.51.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu G, Walker DH, Jupiter D, Melby PC, Arcari CM. A review of the global epidemiology of scrub typhus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0006062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song SW, Kim KT, Ku YM, Park SH, Kim YS, Lee DG, et al. Clinical role of interstitial pneumonia in patients with scrub typhus: a possible marker of disease severity. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19:668–673. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2004.19.5.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misra UK, Kalita J, Mani VE. Neurological manifestations of scrub typhus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:761–766. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin JY, Kang KW, Moon KM, Kim J, Choi YJ. Predictors of acute myocarditis in complicated scrub typhus: an endemic province in the Republic of Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33:323–330. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KY, Song JS, Park EH, Jin GY. Scrub typhus: radiological and clinical findings in abdominopelvic involvement. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35:101–108. doi: 10.1007/s11604-016-0607-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thipmontree W, Suwattanabunpot K, Supputtamonkol Y. Spontaneous splenic rupture caused by scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:1284–1286. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KR, Park WK, Chang JC, Cho JH, Kim JW, Hwang MS, et al. The pathologic splenic rupture of a patient with scrub typhus: a case report. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2008;58:83–86. doi: 10.3348/jkrs.2008.58.1.83. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Settle EB, Pinkerton H, Corbett AJ. A pathologic study of tsutsugamushi disease (scrub typhus) with notes on clinicopathologic correlation. J Lab Clin Med. 1945;30:639–661. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park MJ, Lee HS, Shim SG, Kim SH. Scrub typhus associated hepatic dysfunction and abdominal CT findings. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:295–299. doi: 10.12669/pjms.312.6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1114–1121. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartlett A, Williams R, Hilton M. Splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: a systematic review of published case reports. Injury. 2016;47:531–538. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imbert P, Rapp C, Buffet PA. Pathological rupture of the spleen in malaria: analysis of 55 cases (1958–2008) Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zingman BS, Viner BL. Splenic complications in malaria: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:223–232. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durey A, Kwon HY, Park YK, Baek J, Han SB, Kang JS, et al. A case of scrub typhus complicated with a splenic infarction. Infect Chemother. 2018;50:55–58. doi: 10.3947/ic.2018.50.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang JH, Lee CS. Incidentally discovered splenic infarction associated with scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:435. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapoor S, Upreti R, Mahajan M. Splenic infarct secondary to scrub typhus: a rare association. J Vector Borne Dis. 2019;56:383–384. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.302044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goyal MK, Porwal YC, Gogna A, Gulati S. Splenic infarct with scrub typhus: a rare presentation. Trop Doct. 2020;50:234–236. doi: 10.1177/0049475519892092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung JO, Jeon G, Lee SS, Chung DR. Two cases of tsutsugamushi disease complicated with splenic infarction. Korean J Med. 2004;67:S932–S936. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tayade A, Acharya S, Balankhe N, Ghule A, Lahole S. Splenic infarction complicating scrub typhus. J Glob Infect Dis. 2020;12:238–239. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_27_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raj SS, Krishnamoorthy A, Jagannati M, Abhilash KP. Splenic infarct due to scrub typhus. J Glob Infect Dis. 2014;6:86–88. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.132055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s the findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.