Novomessor ensifer

| Novomessor ensifer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Formicidae |

| Subfamily: | Myrmicinae |

| Tribe: | Stenammini |

| Genus: | Novomessor |

| Species: | N. ensifer |

| Binomial name | |

| Novomessor ensifer (Forel, 1899) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The natural history of this species was studied by Kannowski (1954).

Identification

Keys including this Species

Distribution

Latitudinal Distribution Pattern

Latitudinal Range: 31.96276667° to 17.810402°.

| North Temperate |

North Subtropical |

Tropical | South Subtropical |

South Temperate |

- Source: AntMaps

Distribution based on Regional Taxon Lists

Neotropical Region: Mexico (type locality).

Distribution based on AntMaps

Distribution based on AntWeb specimens

Check data from AntWeb

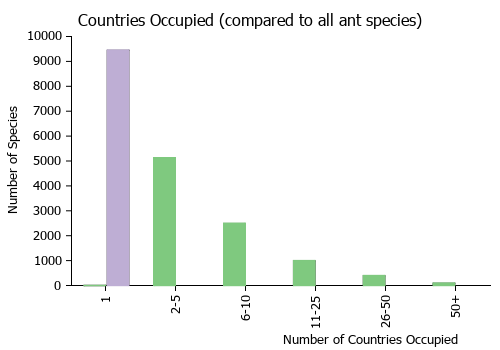

Countries Occupied

| Number of countries occupied by this species based on AntWiki Regional Taxon Lists. In general, fewer countries occupied indicates a narrower range, while more countries indicates a more widespread species. |

|

Estimated Abundance

| Relative abundance based on number of AntMaps records per species (this species within the purple bar). Fewer records (to the left) indicates a less abundant/encountered species while more records (to the right) indicates more abundant/encountered species. |

|

Biology

The following natural history information is from a study of this species by Kannowski (1954). These details were reported under the name Novomessor manni.

The terrain in which manni occurs consists of basins and low mountains on the Pacific slope between the pine-oak forest on the interior mountains and the Pacific Ocean. The city of Colima lies in one of these basins, and it was in this basin that our study was made. The soil consists of many large stones buried in rather coarse sand. The precipitation is periodic, with a wet season in late summer and fall and a dry season in the spring. The plant association occupying this habitat is an arid scrub-thorn forest consisting of two strata of plants: (1) an upper stratum of shrubs and trees which forms a virtually level surface 15 to 25 feet in height, broken only by scattered tall cacti (Lemaireocereus); (2) a sparse to moderately abundant ground cover of low herbs and grasses.

This arid scrub-thorn forest occurs below 5000 feet on the Pacific slope from northwestern Jalisco to Guerrero. Its floristic composition may vary from one part of the range to another, but the basic structure remains the same. Hubbell's specimen was collected in a dry pastured area on a stony hillside bearing Acacia shrubs, Opuntia and other cacti, and foot-tall grasses.

Nests of manni are numerous in the basin at Colima, but their abundance decreases sharply in the mountains. My wife and I found several nests on a sandy hillside, but were unable to locate any nests in parts of the same hillside where sand had not accumulated. We also looked for nests in the sandy coastal plain southeast of Manzanillo, but the absence of large stones buried in the soil appears to prevent manni from founding nests in this area. Thus, it seems that a soil containing both sand and buried stones is necessary for the establishment of manni nests.

We were unable to excavate completely any of the large nests. The stony soil made the job impossible with ordinary collecting equipment in the short time available; however, the data obtained from the complete excavation of a small incipient colony and the partial excavation of three large colonies seem sufficient to permit interpretation of the structure of the nests in fair detail. The nests were usually situated under one or more stones in the soil. The nest opening was a single hole from one to four inches in diameter at the side of a stone or between two stones. No craters of excavated soil were seen surrounding the openings of nests built under stones. Although over 25 nests of manni were observed in two small areas near Colima, only one nest was found which was not built under a stone on the soil surface. This was built at the base of an Acacia plant and had a recognizable crater surrounding the opening. In all other respects this nest was similar to the others. Each nest had a single wide passageway which descended almost straight down into the soil for several inches and widened out under a stone to form a gallery for the larvae and pupae. The galleries were irregular in shape and quite large, measuring three to eight inches in diameter. The passageway continued deeper into the soil with galleries formed wherever a stone was encountered. How deep these passageways go is unknown. One nest was excavated to a depth of 15 inches, but had to be abandoned when we broke our spade handle. The passageway was still going down with no evidence of horizontal branching.

Larvae and pupae were usually found unsorted in the uppermost galleries. A peculiar feature of the larvae was noted in several nests. Some of them were joined together side by side by hooked hairs which are present on the sides of the larvae, and were so joined that they resembled a small, open-ended, hollow sphere. Such an arrangement is probably an advantage to the workers in moving the larvae about and in keeping them together in a group.

A single incipient colony consisting of a dealate female, 31 workers, 6 pupae, 15 larvae, and 10 eggs was found under a stone. The opening at the base of the stone was one inch in diameter, and the passageway extended down seven inches. Three galleries were noted under buried stones, each gallery containing larvae. The pupae were in the uppermost gallery; the female and the eggs were in the deepest gallery. When discovered, the female attempted to abandon the nest. The workers made no attempt to protect her, but instead began to pick up the brood. Small workers in this nest probably represent the first brood, whereas later broods likely developed into large workers only. Small workers were rare or absent in the larger nests.

Nothing is known of the mating activities of manni. Alate forms were absent in all observed nests in August, and they are not represented in Cantrall's February collection. Neither were pupae of the sexual forms found in August. The larvae in our collections do not seem to be large enough to represent sexual forms. For these reasons I believe that the mating flight takes place in spring or early summer. Since in the Davis Mountains of Texas alates of cockerelli and albisetosus occur in nests in June, it may be that the alates of manni are also produced at this time of the year.

It is unfortunate that only a single incipient colony was found, since much can be inferred on the nest-founding activities of the female by examination of such colonies. I feel certain, however, that the female begins the nest by forming a small gallery under a protecting object, usually a stone, but sometimes a partly exposed root of a woody plant. The dependence upon stones buried in the soil for the construction of a nest supports such a belief. This nest-founding behavior, which is unusual for females of xerophilous species, has recently been observed in Veromessor pergandei by Creighton (1953: 16).

Workers were seen foraging throughout the day (9:00 A.M. to 5:00 P.M.), although their abundance was greatly diminished in the middle of the day, when the air temperature was approximately 95° to 100° F. (the surface temperature must have been considerably higher). Workers foraged in greatest numbers from 9 to 11 A.M. and from 3 to 5 P.M. Since we did not stay at Colima at night, but commuted from Manzanillo each day, nothing is known of the nighttime activities of this ant. Most of the foraging was done on the ground; a few workers were found on low herbage, but they did not seem to feed on the plants. No seeds were found stored in the nests, and no workers were seen gathering seeds. It seems likely that dead insects provide the bulk of the diet. Parts of dead insects were found in several nests. The foraging workers of one nest were watched one morning while they brought three dead insects (an ichneumon fly, a bembicine wasp, and a small moth) to the nest. The workers forage singly and often work 25 feet or more from the nest. On discovering a dead insect the worker immediately starts to pull the food toward the nest. As other workers discover the food, they join in the project, but with a noticeable lack of cooperation. Although each worker attempts to pull the food in a separate direction, eventually the food is somehow brought to the nest. Sometimes the dead insect is accidentally torn apart, and each worker will carry a piece to the nest.

Living mites and collembolans were collected in one nest, but have yet to be identified. Their status in the nest has not been determined.

Castes

Nomenclature

The following information is derived from Barry Bolton's Online Catalogue of the Ants of the World.

- ensifer. Aphaenogaster (Ischnomyrmex) ensifera Forel, 1899c: 59 (w.) MEXICO (Michoacan).

- Type-material: syntype workers (number not stated).

- Type-locality: Mexico: Michoacan (no collector’s name).

- Type-depository: MHNG, possibly also MSNG.

- Mackay & Mackay, 2017: 466 (q.).

- Combination in Aphaenogaster (Deromyrma): Emery, 1915d: 71;

- combination in Novomessor: Demarco & Cognato, 2015: 8.

- Status as species: Emery, 1915d: 71; Emery, 1921f: 65; Kempf, 1972a: 23; Brown, 1974b: 46; Brandão, 1991: 326; Bolton, 1995b: 69; Demarco & Cognato, 2015: 8; Mackay & Mackay, 2017: 465 (redescription).

- Senior synonym of manni: Brown, 1974b: 46; Brandão, 1991: 326; Bolton, 1995b: 69; Demarco & Cognato, 2015: 8; Mackay & Mackay, 2017: 465.

- Distribution: Mexico.

- manni. Novomessor manni Wheeler, W.M. & Creighton, 1934: 353, pl. 1, fig. 2 (w.) MEXICO (Colima).

- Type-material: holotype worker.

- Type-locality: Mexico: Colima (W.M. Mann).

- Type-depository: MCZC.

- Wheeler, G.C. & Wheeler, J. 1960b: 10 (l.).

- Status as species: Kempf, 1972a: 166.

- Junior synonym of ensifer: Brown, 1974b: 46; Brandão, 1991: 326; Bolton, 1995b: 71; Demarco & Cognato, 2015: 8; Mackay & Mackay, 2017: 465.

Unless otherwise noted the text for the remainder of this section is reported from the publication that includes the original description.

Description

Worker

Wheeler and Creighton (1934) as Novomessor manni - Length 10 mm.

Head, exclusive of the mandibles, slightly less than twice as long as broad, widest just behind the eyes, the sides of the anterior half straight and only slightly tapering inward from the eye to the insertion of the mandibles; posterior to the eyes they are feebly convex and converge sharply toward the occiput where they form a flanged collar similar to that in certain species of Aphaenogaster (arancoides etc.). Clypeus rather flat above, truncate anteriorly with the lateral edges feebly arcuate. Mandibles large, triangular, with three apical teeth, the innermost tooth notably smaller and more obtuse than the other two, the remainder of the masticatory margin irregularly serrate but without definite denticles. Eyes prominent, strongly convex, subcircular in outline, placed slightly in front of the middle of the head. Frontal carinae well developed, strongly divergent anteriorly, parallel behind. Frontal area well defined, slightly but clearly depressed. Antennal scapes feebly curved, their thickness evenly increasing from base to tip. In repose they surpass the occipital margin by a distance equal to one quarter of their entire length. Funiculus filiform, the first joint much longer than any of the succeeding joints, which notably decrease in length though only slightly increasing in thickness from base to apex.

Thorax without sutures. Seen from above the pronotum is campanulate and twice as wide as the immediately adjacent portion of the mesonotum. Sides of the mesonotum moderately divergent behind, slightly wider than the epinotum, the latter narrowed in front but rectangular behind. Seen in profile the promesonotum forms a single feeble and somewhat irregular convexity, the epinotum is flat throughout except for an anterior sinuosity where it joins the mesonotum. Epinotal spines long, their apical two-thirds slender, their bases somewhat thickened. Seen in profile they are virtually straight and almost parallel with the dorsum of the epinotum. Seen from above they are feebly divergent and slightly curved inward, with their thickened bases set close together.

Node of the petiole in profile low and evenly rounded above, its anterior face meeting the thick and tapering anterior peduncle in a well-marked angle, its posterior face confluent with the short posterior peduncle. Postpetiole in profile much narrowed in front, the dorsum feebly convex, the ventral surface straight in its anterior half and feebly sinuate behind. Seen from above the node of the petiole is sub oval, scarcely wider than the peduncle, and less than half as wide as the pyriform postpetiole. Gaster large, oval.

Head and thorax ferruginous; petiolar nodes, epinotal spines, and legs clear yellowish red; antennal scapes and to a lesser extent the funiculi sordid, reddish brown; abdomen piceous brown. Mandibles shining, with feeble striae and numerous, coarse, piligerous punctures. Clypeus with a few, coarse, longitudinal striae which converge at its anterior edge. Head with numerous, coarse, wavy rugae extending diagonally from the genae across the front and uniting to form continuous, sharp, transverse rugae on the vertex. Area just behind the frontal carinae with longitudinal rugae. The spaces between them on the front and vertex are granulose, giving this portion of the head a duller appearance than elsewhere. Entire thorax strongly shining, the pronotum feebly shagreened; mesonotum and epinotum with prominent transverse rugae. Area between the base of the epinotal spines smooth. Petiole and postpetiole finely granulose, dull. Gaster smooth and very shining with sparse and minute, piligerous punctures. Hairs golden, sparse, short, stout, erect, or suberect; virtually absent on the mesonotum and epinotum, no longer on the under surface of the head than elsewhere. Tarsi and scapes covered with numerous rather fine, sub erect hairs; funiculi pubescent.

Type Material

Novomessor manni type - Described from a single worker taken by Dr. W. M. Mann at Colima, Mexico.

References

- Brown, W. L., Jr. 1974b. Novomessor manni a synonym of Aphaenogaster ensifera (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Entomol. News 85: 45-47. (page 46, senior synonym of manni)

- Demarco, B.B. & Cognato, A.I. 2015. Phylogenetic analysis of Aphaenogaster supports the resurrection of Novomessor (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 1–10 (doi:10.1093/aesa/sau013).

- Emery, C. 1915k. Definizione del genere Aphaenogaster e partizione di esso in sottogeneri. Parapheidole e Novomessor nn. gg. Rend. Sess. R. Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna Cl. Sci. Fis. (n.s.) 19: 67-75 (page 71, combination in Aphaenogaster (Deromyrma))

- Forel, A. 1899e. Formicidae. [part]. Biol. Cent.-Am. Hym. 3: 57-80 (page 59, worker described)

- Kannowski, P. B. 1954. Notes on the ant Novomessor manni Wheeler and Creighton. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 556:1-6.

- Wheeler, W. M.; Creighton, W. S. 1934. A study of the ant genera Novomessor and Veromessor. Proc. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 69: 341-387.

References based on Global Ant Biodiversity Informatics

- Castano-Meneses, G., M. Vasquez-Bolanos, J. L. Navarrete-Heredia, G. A. Quiroz-Rocha, and I. Alcala-Martinez. 2015. Avances de Formicidae de Mexico. Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

- Dattilo W. et al. 2019. MEXICO ANTS: incidence and abundance along the Nearctic-Neotropical interface. Ecology https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2944

- Fernandes, P.R. XXXX. Los hormigas del suelo en Mexico: Diversidad, distribucion e importancia (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).

- Kempf, W.W. 1972. Catalago abreviado das formigas da regiao Neotropical (Hym. Formicidae) Studia Entomologica 15(1-4).

- Vásquez-Bolaños M. 2011. Lista de especies de hormigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) para México. Dugesiana 18: 95-133

- Wheeler W. M., and W. S. Creighton. 1934. A study of the ant genera Novomessor and Veromessor. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 69: 341-387.